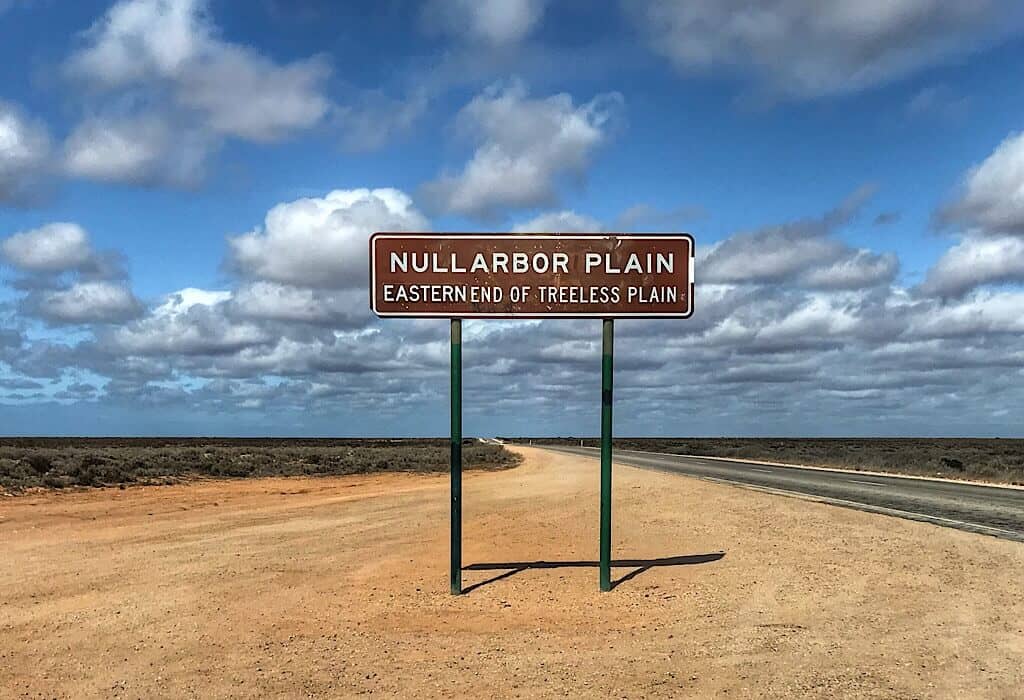

Two roads converge into one seemingly endless stretch of bitumen that connects the east to the west across the bottom of the continent of Australia. One road with no intersections, no mountains to climb, no major curves for 1,203 km (748 miles). That’s longer than the drive from Washington DC to Florida.

NEW FEATURE! Listen to this article. Scroll to the end for the audio file or click here to jump to the end.

Surrounding the road is a vast plain of sand and scrub brush. If I were color blind it would almost seem as though we were crossing the ocean on a road, an ocean made of desert the distant horizon fading away in its unchanging line against the blue sky. An ocean road with camels, kangaroos, wombats, emu, and an occasional cow crossing it.

The limestone desert plain

This road crosses the Nullarbor, a limestone cleft that covers 77,000 square miles. The word Nullarbor comes from the Latin ‘Nullus’ and ‘Arbor’ meaning ‘no trees.’ The Aboriginal word for this plain is ‘Oondiri’ meaning ‘the waterless.’ The average annual rainfall for the area is about 8 inches.

The southern edge of this treeless plain continues in its flat unchanging stretch across the horizon where it ends in a dramatic cliff dropping to the ocean far below on The Great Australian Bight. On a map, this edge of the continent looks like someone took a large bite out of a cookie. From the ground, one can almost see the teeth marks in the perpendicular cliffs of the Bight.

The experience of utter remoteness

I can hear a tinge of reverence when people talk about crossing the Nullarbor. Many we have talked to here in Australia have never crossed it. Others proudly puff out their chests a little when they tell us they have crossed it a few times. It is not arrogance, but a sense of accomplishment, a good feeling. It is an experience. Something about the Nullarbor does that. Maybe it is the utter remoteness, the vast open exposure of limestone bedrock that stretches in all directions as far as the eye can see.

We have been anticipating this quintessential outback experience for some time now. Watching the weather, we waited for a week with cooler temperatures predicted. Once we started there would be no shade to escape into, no accessible beaches to swim and cool down in. As the Aboriginal name goes it is waterless.

This passage would be a trek across land that can quickly become an oven and we have no air conditioning. We topped off our water tanks and bottles, filled up our fuel tank and stocked up on our food supply. Then we pointed Lil’ Beaut west and headed out of Ceduna at the top of the Eyre Peninsula where two roads converge into one.

The last settlement

About 75 Kilometers from Ceduna is the town of Penong, population 289 (2016 consensus). It is the last settlement before the Western Australian border 406 km further down THE road, but that border is not even near the end of this road.

We stopped in Penong to view the windmill museum. It is a small park containing donated windmills used by farmers as far north as Alice Springs (near the center of Australia). This is a tribute to the whirling workhorse used to pump water from deep underground. Some farmers have replaced windmills with solar panels but quite a few working windmills can still be seen in the outback.

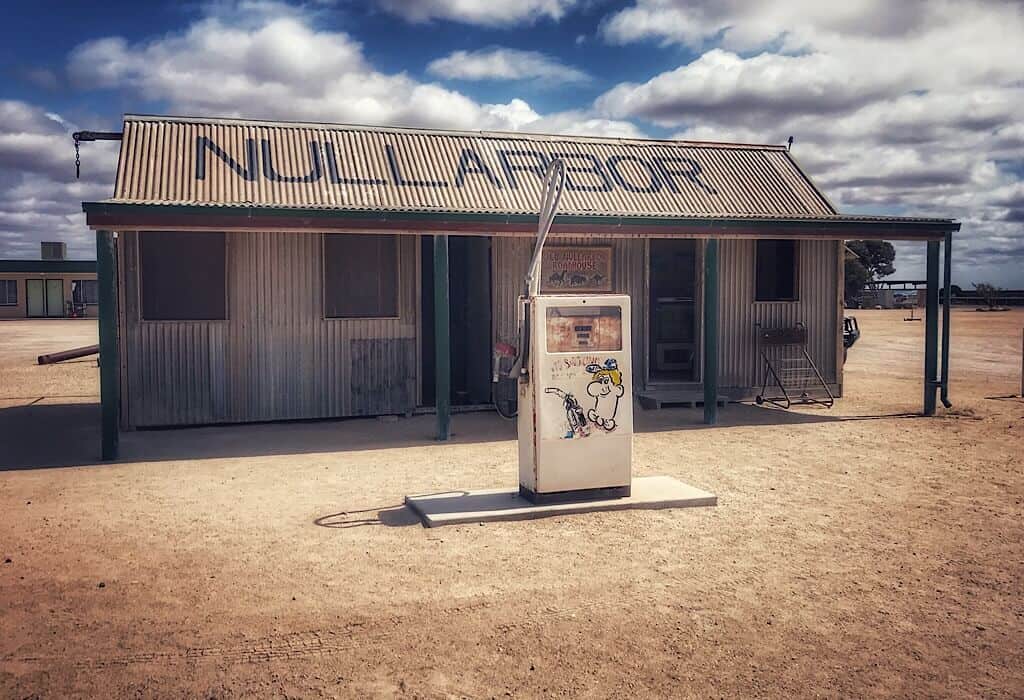

Roadhouses

There are a few stations along this long narrow road where fuel and food can be purchased. A couple of times the road widens and there are signs that the two-lane pavement also doubles as an emergency landing strip.

Prices at the roadhouses are almost twice what would be paid elsewhere, but they are reasonable given the difficulty of supplying and maintaining these conveniences for travelers. I’m sure the business also need to (and should) pay a premium to those who choose to stay and work along this road.

A few times we spotted lone 20-liter water jugs sitting beside the road. Emergency supplies for anyone who breaks down. They could save a life.

The driver of every caravan and RV we pass waves, it’s almost compulsory. There is a camaraderie in following this road. Everyone who is on it is headed to where you are going or where you came from. It is a shared experience.

Time becomes irrelevant

Occasionally there are dirt tracks extending from THE road. They reach out toward the horizon, what they pursue can not be seen from this singular bitumen journey. The paved two-lane road shimmers in the distance with the familiar liquid movement of a mirage.

Driving a fairly straight road for days across a plain of low scrub brush might sound boring to some, but I found it utterly fascinating. There is a beauty and an otherworldly feel to the sheer size, a size that can not be understood from a single viewpoint. It is the passing of days that gives breadth to the expanse that doesn’t end hour after hour. Time slows to irrelevance and space expands filling our minds with wonder at the vastness.

Mysteries beneath

Despite the sameness on the surface, there are mysteries that lay beneath, caves and sinkholes that we were excited to explore.

Rainwater picks up carbon dioxide from the air and soil creating a weak acid. This acid then seeps into limestone cracks slowly dissolving it creating caves and sinkholes. The Nullarbor is the world’s largest single exposure of limestone bedrock and there are geological wonders to explore beneath her surface.

Trin slowed Lil’ Beaut and I looked around, there were no cars behind or in front of us as far as the horizons. Then I saw what he was slowing for, a narrow dusty track to the right of the road. We turned onto the rutted stone strewn track. Dry branches from the low bluebrush and saltbush vegetation scratched against both sides of Lil’ Beaut as we drove further.

We both kept our eyes out for sections of the track that appeared to be too soft or ruts too deep. We did not want to get our bus stuck out here. A few kilometers from the paved road the dirt track widened into a small parking area from where we could see what we veered off the road for. Stopping the bus we threw on our shoes and walked to the edge of a massive hole in the ground. We walked around the circumference of the hole, but all of the edges were too steep to descend.

At the next sinkhole, we spotted a footpath along the far edge of the sinkhole. It descended steeply down small ledges and steep scree. Carefully we entered a small cave at the bottom. It was cool and damp.

Camping

Our first two nights along THE road we pulled off onto dusty tracks that wound back into the bush and parked for the night. All was quiet except for the occasional road train going by in the night.

On the third night, we navigated a dusty track that leads to the cliff edge of the plain. We had been following various tracks throughout the last two days to see the cliff-side views as we progressed towards Western Australia. On this night we parked near the cliff edge to watch the sunset over the horizon in front of us. Wind gusts came through like passing trains rocking the bus back and forth squealing through our open vents. Then all would be still and only the sound of waves far below us could be heard crashing against the cliffs in a distant refrain.

The open space, absence of towns and lack of other human beings gives campers freedom not felt in more populated areas. In the morning as we were getting ready to leave we heard another caravan park along the cliff edge. Trin started up Lil’ Beaut began to drive out. As we drove past the other caravan, its occupants popped out. It was a middle-aged couple almost skipping to the edge of the cliff in their joy of freedom. Happiness emanated from their every movement. They were both as naked as the day they were born. We feel freedom here, but not quite that much. We will need to clean our dashcam later.

Border Crossing

We have heard stories about border crossings between states in Australia and heard rumors of major fines for those who try to take forbidden produce or goods across the border. Australia is serious about keeping pests from spreading and Western Australia is free of some of the pests that plague the east coast. We read the list multiple times to make sure we were in compliance.

The border agent came into Lil’ Beaut to have a look inside our refrigerator. Trin pointed out our commercially-packed carrots and the agent asked if we had any garlic. Trin pointed to the garlic he had peeled the night before and placed it in a container in the fridge.

“Good, it looks like you guys read the book and know what you are doing. You are good to go,” the agent said.

He was friendly and asked about our travels. A very pleased smile spread across his face when we told him how much we were enjoying Australia.

We were now a little over halfway across this long road.

Bats and Dingos

Turning left onto another corrugated dirt road we drove towards the Madura caves. Here the opening to the sinkhole was much larger and the east side sloped giving us easy access to the base of the sinkhole.

At the bottom of the sinkhole, we ducked down and squeezed through a tiny opening in the rocks. After crawling through we found ourselves in a large cave, in the distance we could see light coming in from small holes in the ceiling. We walked along the sandy bottom that had patterns indicative of creek bottoms telling us that water flows through here during the rains. Very little rain falls in this region, but it often comes in a deluge when it does come.

The deeper we walked into the cave the cooler and damper it became. Some of these sinkholes and caves descend below the water table and are explored by expert divers. We stopped when we accidentally disturbed a colony of bats. They began to stir and fly around, so we retraced our steps and crawled back out.

Within this same sinkhole, another cave opened to the left. This cave had a large opening but only extended about half of a football field under the limestone cleft. Bones were scattered all around the opening of the cavern. They appeared to be of kangaroos. As I progressed deeper the stench of fresher carcasses assaulted me. There were dead kangaroo scattered all over the floor of this den. Some people believe this is a dingo den.

Paleontological Wonder

After exploring the caves we drove further into the desert away from the highway. We stopped to open a gate in the dingo fence, drive-through and close it behind us. The fences help keep dingoes from killing livestock in the area.

We drove another few kilometers to a paleontological dig that I was excited about seeing.

Paleontologists have cleared an area of topsoil away down to the limestone surface. The topsoil is only two to three feet deep and amazingly the limestone surface is well preserved with minimal erosion from the time it lay on the ocean floor. Shells litter the ground giving evidence of the abundant sea life that once thrived above this surface.

Caiguna

Caiguna is a station beside the road with fuel pumps, restrooms, a caravan park, a small convenience store, a restaurant, a hotel and a couple of trees. The complex looks like a small ghost town one might see in an old western. Walking from one end to the other could be done within the space of sixty seconds.

I picked up a squeegee at the fuel pump to wash our windows, it was in shreds and covered with slime. The squeegee at the next pump was just as bad. The attendant next to me was taping signs to the pumps that read “Sorry, no more gas.”

I walked to the last remaining squeegee bucket to find it in the same condition as the other two.

“Sorry we have some on order, they just haven’t arrived yet,” the attendant said as he walked by.

This roadhouse is a long way from anywhere.

Just after Trin paid for our fuel the power went out and no one else could pump any fuel.

I waited outside at a picnic table with a bit of shade while Trin used the restroom. A biker sat at the table near me reading and also taking a break in the shade.

“Do you know what time it is?” I had seen a check time zone note on the map I was looking at and thought I should double-check our clocks.

“I have no idea,” he laughed. “My watch says it is 2 PM over in WA, I have no idea what time it is here.”

My phone said 4:30 PM. somewhere we missed a time zone change or two but it wouldn’t have altered anything. We get up with the sun and camp before it goes down. It’s all the markers we need. How different from the life we lived only four years ago when seemingly every half hour was nailed to a deadline.

Fun Fact: Did you know that the longest gulf course in the world stretches across the Nullarbor plain? You can even borrow gulf clubs at one end of the course and return them 1,365 km later at the other end.

Fire

Just a few kilometers from Balladonia we saw a column of smoke rising in the air. This road had been closed for almost two weeks due to uncontrolled fires crossing the road and essentially blocking all traffic between West and South Australia. We had been keeping track of the fire maps and waited a week after the road opened before we began our trek across the Nullarbor. I checked my phone for signal, nothing. Maybe there would be some at the Balladonia station.

As we approached the station I could see smoke in the brush along the ground to the left of the road and knew that the fire was not too far away. We gained a signal at Balladonia but the fire was not even reported on the Western Australia map yet.

The attendant told us that a fire had just started about 15 kilometers down the road where we came from. He said firemen were on their way from Norseman, a town 220 kilometers to the west.

We had planned to camp about 50 km west of here towards Norseman and asked him if he thought it was safe.

“It all depends on the way the wind blows,” he shrugged.

We parked at the Newman Rocks area to camp for the night and took note of the smoke on the horizon. We walked out to the water holes nearby where camels are said to come in for a drink. It was a short walk but by the time we got back to Lil’ Beaut, the entire horizon was in a brownish haze. We had some signal here so I checked the WA map again. The fire was finally reported, it advised caution and said firemen are on the way.

One other caravan was parked near us, its owner was also looking at the horizon so we walked over to discuss what we were seeing.

He had just come from Norseman and was unaware that a new fire started up.

“The smoke I saw earlier was gray, this cloud on the horizon is brown. Do you think it is just dust picked up in the wind?” I asked him.

We studied it a while. We could smell the dust, we did not smell smoke so we agreed that it was most likely a dust storm that had picked up.

Trin and I decided that driving in the dust storms in now what was very strong winds might be more dangerous. We decided to wait out the wind. Our neighbors said they would honk if they decided to leave because of fires to alert us.

The winds died down by 10 PM and the horizon cleared, alerts on the map did not change so we stayed for the night.

The end of the road

With nothing much to get in the way, a 90-mile section of this road is the longest straight road in Australia. There is not even a slight curve for 90 miles.

There are no curves but this section of the road felt a little differently than the last 1,000 kilometers that we just traversed from Ceduna.

Along this straight section, we stopped to see a hole in the ground that breathes. The temperature outside was almost 90℉. Beside the road was a very small sinkhole. Air was blowing out of it at a high speed. We stood beside it and it felt like air conditioning running at full power. We basked in the coolness for a while before moving on.

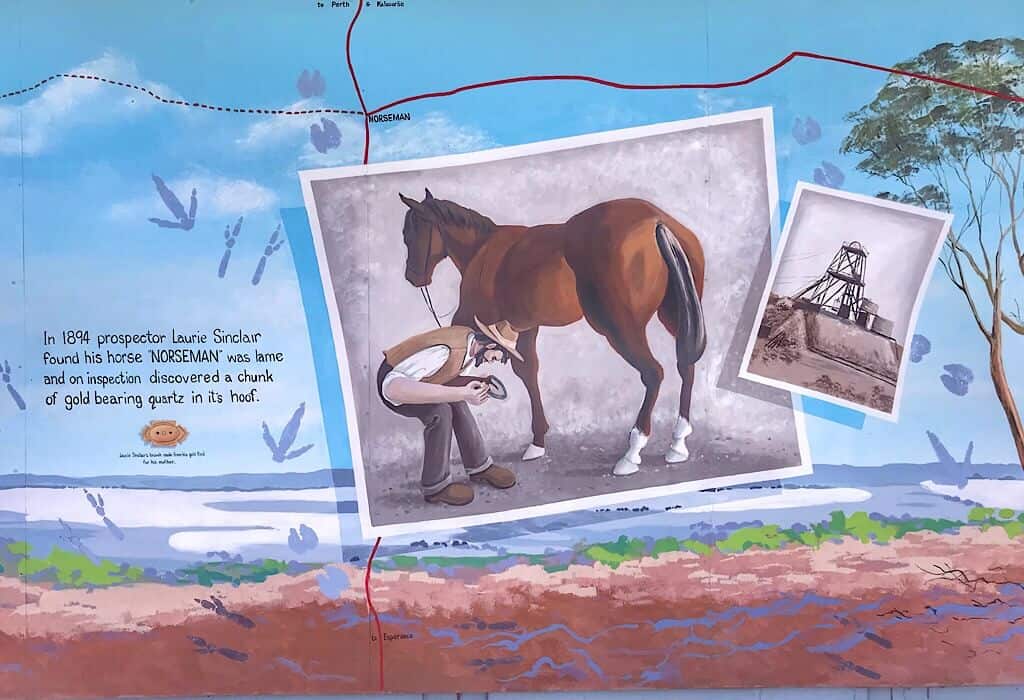

Approaching the town of Norseman felt like a major event. It had been six days since we left Ceduna. Six days on one road and it ended in a T. We had the option of turning north to Kalgoorlie or south to Esperance. Our water and food mostly depleted by now had lasted the journey. One journey ended, but our exploration of Western Australia now begins.

Just loving your journey guys! You spoke of a border rules book, where do you acquire these from? Just trying to get a heads up, before we embark on our journey.

You can find most of what you need here https://www.interstatequarantine.org.au/travellers/interstate-quarantine/ We picked up a printed copy at an information center.

Wow! Traveling this road would be exciting. Just looking at vast flat land is . . . . . . . . I don’t have any words to describe it – but definitely exhilarating. Keep on enjoying this adventure in your life.

The flat horizon in all directions was a very cool experience

It’s so lovely to read about our country through your eyes. Keep on having a wonderful time here. There is so much to see.

Thank you, This country has surprised me. It has so much more than I dreamed it would

Looks interesting, added to the bucket list. I’ve never been west of port Campbell in Oz.

I found it fascinating. If you do the trip Mt. Gambier is worth a stop on your way. Then after you reach Noreseman turn left to La Grand NP if you have time. I’ll write up a post about the beaches here they are unbelievable.

Welcome to W.A. 🙂

Great storytelling Bonnie!

I could feel not only the emptiness of the landscape but how you felt being immersed in it!

I must admit to being one of those Aussies who have never driven the Nullabor – it is the stuff of legends.

I have friends who have taken the Indian Pacific – the train that joins the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.I used to live minutes from the end of the line in Perth, and now I live minutes from the other end of the line in Sydney.

Looking forward to hearing your stories as you travel W.A. – I am sure you will have lots of stories about Kalgoorlie. If you research C.Y. O’Connor you might have an interesting linking story between Perth and Kalgoorlie.

Can’t wait till your next installment

Shaun

Thank you Shaun! The train would be an interesting journey as well but the passengers wouldn’t get to stand on that cliff edge. I would miss that.

Thank you for the tip about C.Y. O’Connor. I have some research to do now 🙂

My father drove the Nullabor in a 1930’s Riley 9, back 30-odd years ago when I was a kid.

One day I’ll do it…

🙂

That sounds epic 🙂