The smell of old wood and rusted walls wafts lightly in the breeze. A gentle wind cools the desert air and plays an eerie song with the loose clapboards and the corroded panels of the ancient metal roof. The song seems to be the voices of lives once vibrant in this town now only inhabited by rumored ghosts. They tell the tales of life from long ago here in the dust of the Atacama desert.

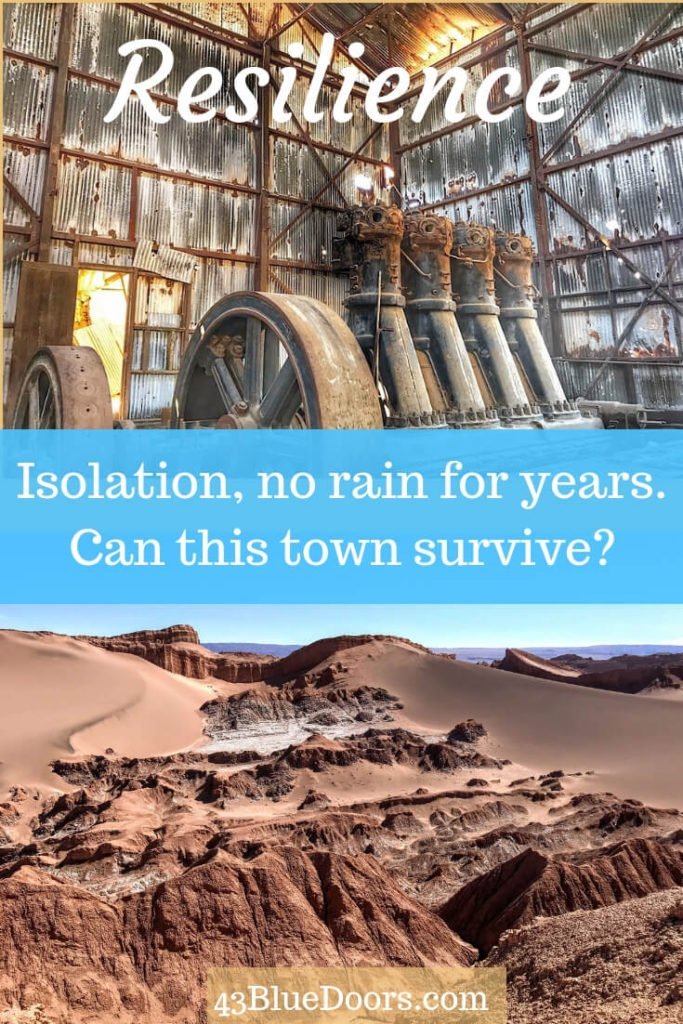

Trin and I stood in wonder gazing at the massive machinery that supplied electricity to the once-thriving town of Humberstone and its saltpeter mine.

Humberstone was established in 1862 and features rows of housing, a large theater, a marketplace, a hotel, and even a massive swimming pool. In 1910, 65% of the saltpeter production in the world was Chilean.

Now, save for a smattering of tourists, nothing but dust blows down the streets of this town. The walls are crumbling. Rust has created cottage cheese holes in the metal roofs allowing sunlight to filter through the dust hanging in the air giving it the feel of an aftermath in an old western shootout.

One would think the desert finally had her way and reclaimed its silent, parched earth. If a stranger wandered in they might surmise that a lack of water led to her demise, but he would be wrong.

THE CHILLY CHILEAN DESERT

Upon arrival into the Atacama desert, the driest non-polar desert in the world, I have been fascinated with the thriving cities and towns in this region. The Atacama Desert receives an average of 0.004 inches of rain a year. Some regions like the Valley of the moon have not seen rainfall in over 100 years. My first questions were: how do they survive without rainfall? Where do they get enough water?”

I’ve been through Death Valley in the Mojave Desert of California. It receives 1.5 inches of rainfall a year and is among the hottest places on earth. The Atacama is 10 times drier than Death Valley of the Mojave. I’ve spent quite a bit of time in various deserts of North America and have come to generally associate deserts with heat.

Arriving in the Atacama desert here in South America I expected much of it to be hot. I was wrong. In fact my coldest night here in South America, a night I thought I might die, was spent in the Atacama Altiplano just outside of the Salt Flats in Bolivia. The Atacama desert has completely fascinated me because of its climate and innovative water sources that the towns have had to come up with to thrive in the desert.

Our first stop in Chile was the San Pedro area. The highest elevation spots are downright COLD, but the town of San Pedro is pleasant during the day and just a bit chilly at night. It is stunningly beautiful.

Where the Desert Meets the Ocean

Here in Iquique at sea level on the edge of the Atacama desert, the temperature is consistent during the day ranging between 59°F to 79°F (yearly average). This city rests by the sea and is built almost like a stadium on the edge of a mountain. Its theater is the daily sunset that paints the sky with shades of pastel, and the Camanchaca fog whispering of rain that will never come. Behind Iquique is a steep mountain with one of only two major roads into and out of Iquique. The mountain hems in the city separating it from vast desert lands that contain very little life.

Between the steep backdrop of the surrounding mountain and the city itself lays a sleeping dragon. Or at least that is the legend our host family told us. Macarena, the smart, teenage girl, was showing us a painting of the beautiful sand dune that lay just in front of the mountain and encroaches on the city of Iquique. It is called Cerro Dragon (Dragon Hill). She smiled conspiratorially as she told us that an old dragon fell asleep eons ago just behind the city and over time was covered with sand. She knew it was a fairy tale but if you gaze at the dunes one could just make out the spiny ridge of a medieval creature.

Still, where do they get their water?

A Cool Desert City

The city of Iquique has a population of 180,000 (2012 census). The average daily percent chance of rainfall is 0%. No one here owns an umbrella.

The breeze coming from the Humboldt current keeps the desert air cool. The Humboldt current is frigid water that is swept northward from Antarctica by trade winds. It hugs the shores of Chile and the lower part of Peru, and then a portion of it heads off to the Galapagos Islands. This current is a major reason for the spectacular array of wildlife in the waters around the Galapagos islands.

The cold waters drop to as low as 62ºF in August. The breeze from the ocean reminds me of the misting systems (misters) employed by fancy restaurants in hot desert cities like Scottsdale, Arizona. They cool the air and provide comfort to the customers.

The ocean water is not always that cold. Upwellings in January and February bring the warmer water from underneath the Humboldt current toward the shore raising the temperature of the coastal waters to as high as 73ºF.

This current that runs along the west side of the Atacama desert along with the height of the Andes mountains to the east is the primary reasons for the lack of rain in this region. It is quite fascinating to read about the weather and geological patterns of the earth that create this desert.

This current gains its strength and direction from El Niño and La Niña, both largely impacted by solar storms. To truly understand the global patterns of our weather we must also understand the seasons of the sun. Our universe is so amazing.

Ancient Aquifers

Iquique obtains its water from an underground aquifer (bodies of permeable rock which can contain or transmit groundwater) believed to have been filled by melting glaciers of the Altiplano long since gone. Some rainfall from the high elevation areas just beyond the desert is thought to filter down in underground waterways recharging the aquifers, but many surmise that water usage from the aquifers is greater than the amount of recharge.

Harvesting the Fog

The camanchaca is fog that rises off the cool waters of the coast and drifts over portions of the Atacama desert. Its microscopic droplets, however, are too small to form raindrops. They tease the land with moisture but never form rain for the parched ground.

Since the time that the Atacama desert was formed nature has understood how to sustain itself. Vertical surfaces of plants and cacti thorn are able to collect moisture from the camanchaca and capture enough water to sustain themselves in this arid region.

Over time people have tried to mimic nature. Parched soldiers during the war in the late 1800s would hang rags from their rifles to capture moisture. Indigenous people would hang animal skins to capture water. In 1956 scientist Carlos Espinosa Arancibia conducted experiments with hanging nets that have microscopic holes to capture the fog. The moisture accumulates and forms water droplets that run in a canal beneath the nets.

Drinking Mist

The experiment to capture fog was so successful that they erected enough nets to supply water to the town of Chungungo. More than 100 people in this town relied on water being trucked in once a week. Now they have water piped directly into their homes they need only to turn on the tap. There is even a brewery in town named the Fog Catcher Brewery that obtains all its water needs from the fog.

The nets are inexpensive and water flows to the town using gravity. Studies continue to try and improve the percentage of water captured. Various desert places in the world have also begun to use this technology to capture fog. It is an environmentally friendly, viable, and inexpensive way to survive in a place where it would otherwise seem impossible to do so.

They drink water from the mist.

What Happened to Humberstone?

The floorboards creaked loudly with our every step. We read every information sign we could find to learn more about this town that now lay in ruins. These ruins show evidence of both the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The town obtained its water from the underground aquifer much like Iquique does today. The presence of a massive swimming pool might even suggest that water was not really an issue here in one of the driest places on the planet.

The town fell on hard times in 1929 due to the invention of synthesized ammonia in Germany. This invention led to the industrialization of fertilizers, dropping the price of saltpeter drastically. This almost bankrupted the mine of Humberstone, but they still didn’t throw in the towel.

They modernized their systems and again became the most successful saltpeter works in 1940. But nothing lasts forever and by 1960 Humberstone was shut down and the town was abandoned leaving it at the mercy of the desert winds.

In 2005, UNESCO declared Humberstone and nearby Santa Laura as a world heritage site and tourism to the town improved. The displays and information boards give insight into life at the time of its greatness and how the saltpeter process worked here.

The Resilience of the Miners

It was dark before we finished our exploration of the Humberstone ghost town. We walked through a bit of desert to reach the highway enjoying the colors of the sunset and talking to a man from the south of Chile who was here on vacation. We planned to either hitchhike back to Iquique or find a bus going that way.

As we waited along the highway we could see the headlights from cars traveling over the mountain in the distance. These cars were likely heading toward the now thriving Escondida copper mine. The saltpeter here was the gold mine of its time but, as with most things, time brings about changes. The people of Humberstone did not just sit around and bemoan the loss. They moved on and found the next opportunity.

Escondida is the largest open-pit mine in the world and produces 5% of the copper for the globe. Gold and silver are also extracted as byproducts of the ore.

Unlikely Survival

The harsh conditions of the Atacama to some may look like a region without hope of life. But if one digs deep they can find refreshing water. Reach high and one can obtain moisture from a fog that refused to give up rain.

What looks like a dry, arid desert is really a land rich in nitrates and minerals, the proverbial “gold mine” of wealth. Its riches can be mined. One may fail, yet another rises to the top.

I have always loved examples of resilience, the survival of a conquering spirit in unlikely places. Together, the people of Chile make thriving cities. They are a happy people that smile as you pass them on the sidewalk. Chileans are resourceful, they adapt to changes and overcome obstacles. They grab the opportunities available to them and make the most out of them.

What an intriguing place. Chile sounds like a great place to visit. Thank you for sharing this blog with all of us.

It really is cool. I had to cut out a bunch of other really cool facts about this area to keep it all relevant, but maybe I’ll find a way to fit them into another post.

What a great post! I loved seeing our area through your eyes and descriptive words.

It is a beautiful place. We are really enjoying Chile.

Wow, we have people in the USA always ask us how we get our water here in Iquique! Very interested for me to learn things about this area of Chile by reading this post! Thanks!

I had to do a lot of research for this post and loved it. I simply had to know where the water came from. Thanks for reading:)